The palapa at Kuyima: dining room and gathering place

Whale watching usually means jostling around on a big boat with 50 other people for a quick glimpse of a whale off in the distance. When I learned it could be different–when I saw pictures of people PETTING whales from little fishing boats–I knew I had to go.

Gray whales endure a 5,000 mile migration–one of the longest migrations of any mammal–to three enormous, tranquil lagoons on the Pacific side of the Baja California peninsula. Sheltered from the surging Pacific, they mate, give birth, and raise and nurse their calves to prepare them for the spring journey back to the Arctic feeding grounds.

Map of Baja’s gray whale nurseries

Bahia Magdalena, Bahia de San Ignacio and Laguna Ojo de Liebre (formerly known as Scammon’s Lagoon) all serve as whale nurseries from December through April. A lively tourist industry, ranging from two-hour boat trips to multi-day packages, lures adventurers from around the globe.

Turtle shell on the beach. Because the sanctuary forbids taking souvenirs, the beach is carpeted with seashells, and there are whale bones too.

Bahia Magdalena, also known as Mag Bay, is the southernmost option and the easiest to access from the resort-friendly southern tip of Baja, Los Cabos.

Laguna Ojo de Liebre and Bahia de San Ignacio comprise the Whale Sanctuary of El Vizcaino, within the enormous El Vizcaino Biosphere reserve. This wildlife refuge, the largest in Mexico, protects 9,625 square miles of unique desert landscape. The strict regulations in action since the sanctuary was established in 1993 merit credit for much of the tremendous recovery of the gray whale population in recent decades.

Many ospreys nest near the lagoon. Coyotes stole their eggs, so Kuyima built nesting towers. In Spanish, it’s aguila pescadora, “fish eagle.”

Some say Bahia de San Ignacio has the friendliest whales. Local outfitters include Kuyima Ecotourismo, Antonio’s Ecotours, Baja Ecotours, and Pachico’s Ecotours.

Most packages last between 4-6 days, and some include spendy direct flights to the lagoon. I’m on a budget, and I’m excited about whales, but I also had other ambitions for my 10-day Baja trip. We settled on Kuyima, where we could rent an outfitted tent for two for $40US a night, and get meals and whale watching trips a la carte. In the end, it was under $500US for two people for two nights, three whale watching trips each, and four meals each. Folks with their own camping gear can pitch tents right by the lagoon, cook their own meals, and save a few bucks. Kuyima also runs a neighboring camp where guests stay in small cabins. Both are right on the beach, steps from the lagoon.

Kuyima’s tent camp. We rented a tent, but other folks brought their own gear or RVs.

Kuyima was perfect for us. Off the grid and powered by solar, they have simple outhouses which were perfectly pleasant, a bathing room where one could take a bucket bath with solar heated water, and a spacious enclosed palapa, where we got meals and margaritas and enjoyed the small library of books about whales and Baja. The staff was helpful, devoted to whales, and spoke English. Our fellow visitors included tourists from Baja and elsewhere in Mexico, Italians, Germans and Americans.

Kuyima cabins, at the adjacent camp.

The sanctuary strictly limits whale watching, to ensure visitors don’t overwhelm the creatures. Only a fraction of the bay is accessible to the pangas (small outboard-powered fishing boats), and the number of pangas in that area at any time is limited. Regulations limit each boat to 90 minutes in the area. Some folks come out for a single boat ride, others stay many nights and take at least two boat rides a day.

But how to get there? The road to Kuyima from San Ignacio is only partly paved, and I had trouble verifying its condition. Kuyima could bring us by van, about 90 minutes, but at unpredictable cost. They charge a fixed price ($110US round trip), to be shared by an unknown number of passengers.

There’s plenty of time to wander the beach at San Ignacio Lagoon.

In the end, my friend and I flew into Loreto with Alaska Airlines. We had our rental car by about 2PM, and drove the 170 miles to the town of San Ignacio by 8PM. We lucked out–our little Chevy Aveo had no trouble navigating the mostly paved road to Kuyima Whale Camp. At $280 and one-and-a-half tanks of gas for nine days, we were happy we decided to rent.

Some call it a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I hope not! The thrill of touching whales, the magic of looking one in the eye, the joy of seeing a calf approach with the playful curiosity of a puppy–I’ll be back! And the bonus–Baja California beckons with its dramatic deserts, soaring mountains (as high as 10,000 feet!), 65 islands and 1900 miles of mostly undeveloped coastline. I intend to see a lot more of it.

Sunset with pelicans and pangas

The tiny town of Elgin, Oregon has an unlikely centerpiece: the beautifully restored classical Elgin Opera House. A rural town born of the timber industry, at the bend of the highway leading from La Grande to Joseph, Elgin is tucked in the scenic Indian Valley between the Eagle Cap wilderness and the lovely Blue Mountains.

The tiny town of Elgin, Oregon has an unlikely centerpiece: the beautifully restored classical Elgin Opera House. A rural town born of the timber industry, at the bend of the highway leading from La Grande to Joseph, Elgin is tucked in the scenic Indian Valley between the Eagle Cap wilderness and the lovely Blue Mountains.  Built in 1911, this colonial revival brick theater was uniquely ahead of its time, designed and built for the dual purpose of housing city government offices and a theater.

Built in 1911, this colonial revival brick theater was uniquely ahead of its time, designed and built for the dual purpose of housing city government offices and a theater. Exterior architectural features include a decorative metal cornice and pilasters flanking the entrance, and the vintage restored interior boasts a soaring ceiling, great acoustics, plush draperies, box seats, an orchestra pit, elaborate backdrops and rococo decor. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places.

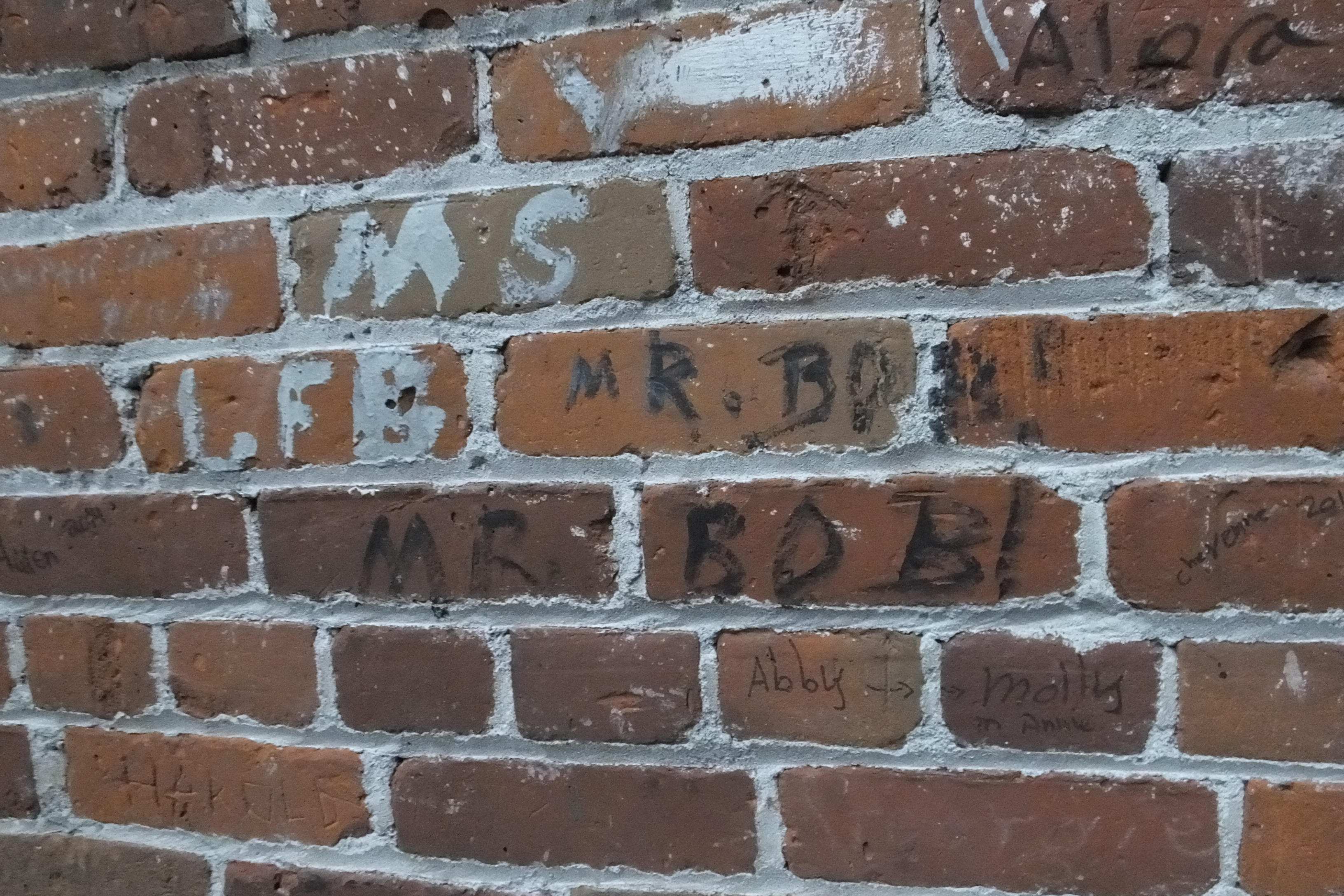

Exterior architectural features include a decorative metal cornice and pilasters flanking the entrance, and the vintage restored interior boasts a soaring ceiling, great acoustics, plush draperies, box seats, an orchestra pit, elaborate backdrops and rococo decor. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places. Honoring tradition, performers have signed the backstage brick walls for over a century. The former jail in the basement serves as costume storage, where barred doors protect suits, gowns and wigs.

Honoring tradition, performers have signed the backstage brick walls for over a century. The former jail in the basement serves as costume storage, where barred doors protect suits, gowns and wigs. After decades as Elgin’s central civic gathering place, it drifted into disrepair. Local forces converged to restore the building in the 1980s, and today the Elgin Opera House brings repeat visitors from as far as Hawaii, California and Idaho to enjoy professionally staged musicals ranging from Oklahoma to Grease to Footloose. This winter, shows include A Christmas Story–the Musical in December and Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat in February.

After decades as Elgin’s central civic gathering place, it drifted into disrepair. Local forces converged to restore the building in the 1980s, and today the Elgin Opera House brings repeat visitors from as far as Hawaii, California and Idaho to enjoy professionally staged musicals ranging from Oklahoma to Grease to Footloose. This winter, shows include A Christmas Story–the Musical in December and Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat in February. A four hour drive from Portland brings you to this charming town, where you can follow a night at the theater with fly fishing on the Grande Ronde River, a journey on the Eagle Cap Excursion Train, or a pedal-powered wilderness ride with the Joseph Branch Railriders–or just relax into the quiet pace of an Oregon back road weekend. You may also eat at the cutest Subway franchise this side of the Mississippi.

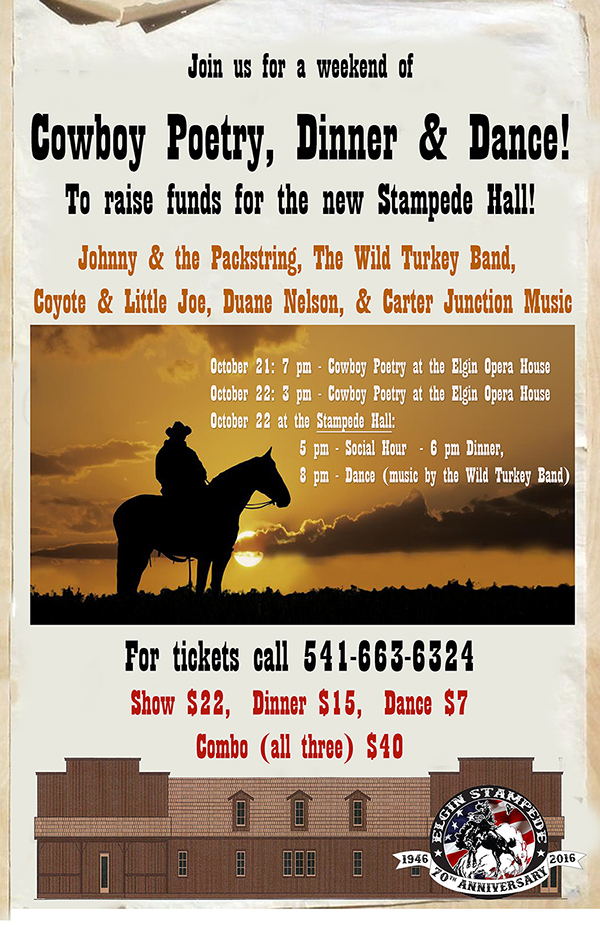

A four hour drive from Portland brings you to this charming town, where you can follow a night at the theater with fly fishing on the Grande Ronde River, a journey on the Eagle Cap Excursion Train, or a pedal-powered wilderness ride with the Joseph Branch Railriders–or just relax into the quiet pace of an Oregon back road weekend. You may also eat at the cutest Subway franchise this side of the Mississippi. For a real taste of the vibrant Elgin arts community, plan a trip this month. On October 21 and 22, the Elgin Opera House presents cowboy poetry, followed by dinner and a dance at the Stampede Hall.

For a real taste of the vibrant Elgin arts community, plan a trip this month. On October 21 and 22, the Elgin Opera House presents cowboy poetry, followed by dinner and a dance at the Stampede Hall.

As the day draws to a close, savvy animal spotters gather by the waterside and wait for elk, wolves, moose and bear to venture near and quench their thirst. Critters abound in this 484-square-mile park–herds of bison graze on the prairie, pronghorn antelope leap through the brush. Study the sky for soaring eagles and osprey, admire jagged peaks mirrored in still water and watch the sinking sun set snow-clad peaks ablaze.

As the day draws to a close, savvy animal spotters gather by the waterside and wait for elk, wolves, moose and bear to venture near and quench their thirst. Critters abound in this 484-square-mile park–herds of bison graze on the prairie, pronghorn antelope leap through the brush. Study the sky for soaring eagles and osprey, admire jagged peaks mirrored in still water and watch the sinking sun set snow-clad peaks ablaze.